Wishing Game Tech Demos to Come Back

These days, advances in video game tech often happen behind closed doors. I wish they were celebrated more.

The GeForce 256 turns 25 years old today, so I figured I’d reminisce a little about the tech driving our beloved games.

Everyone playing video games has their favorite game, and everyone following the games industry probably has a favorite year in video games. For me, it was 2004 - arguably one of the most exciting years in video games. I was a little too young at the time to fully appreciate the most exciting of the releases that year, though I thoroughly enjoyed Need for Speed: Underground, The Sims 2, Pokémon LeafGreen and like a billion amazing demos towards the end of the year.

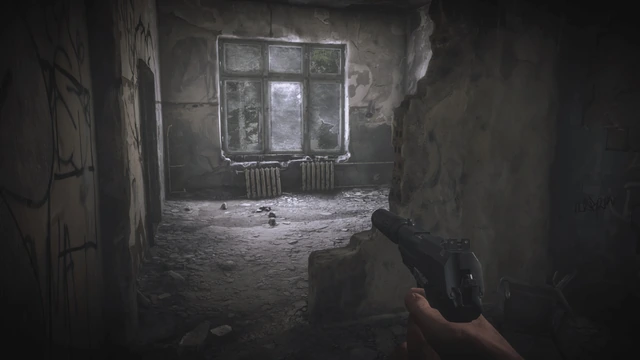

Seeing the E3 show coverage the year before, where some of the games released in 2004 were announced, is what got me interested in game development. Specifically, this screenshot of S.T.A.L.K.E.R. Shadow of Chernobyl (back then still called S.T.A.L.K.E.R. Oblivion Lost) shown exclusively in the E3 coverage of the German GameStar magazine’s 07/2003 issue (p. 22):

The screenshot that started my game development journey. Source

Despite the miniscule size it was printed at in the magazine, I was completely spellbound by it. Especially the rifle’s scope (an OTs-03 SVU-A-lookalike) caught my eye, the folds in the rubber and the irregular shape of it, the reflection in the glass, the little embossed writings on it. Not being able to make out much more, I projected this level of realism onto the whole game in my mind. And it got me interested in learning how people achieved this and birthed a new kind of respect for their work. Naturally, S.T.A.L.K.E.R. with its troubled development history at that point still needed a couple more years in the oven and leaks to happen before being released. Since its humble beginnings it was used to demonstrate the capabilities of GSC Game World’s in-house engine Xray, with numerous trailers showing their advanced AI system, physics simulation, rendering tech, gameplay systems like the day/night cycle and more.

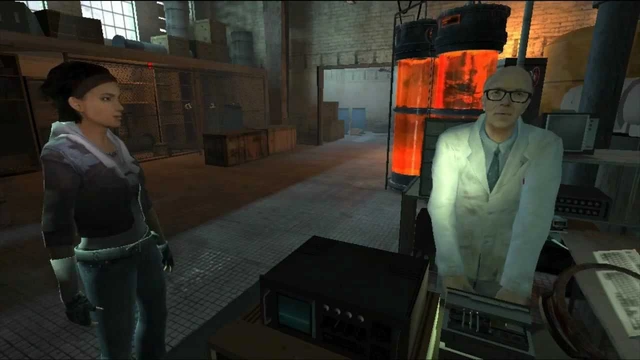

But I digress. Of course, not to forget, at E3 2003 there were also Doom 3’s and Far Cry’s new trailers and the legendary Half-Life 2 demonstration, which was highly realistic in a different way:

A clean version of the presentation made from an original recording released by Valve for Half-Life 2’s 20th anniversary and a reconstructed commentary audio track. There’s also the original clean version without the commentary. Alternatively, Valve Archive has original files released back in 2003.

While S.T.A.L.K.E.R. initially impressed me solely with its image quality, Half-Life 2’s demo displayed a skillful stylization of the realistic and added never-before-seen character interactions and physics into the mix. This demo touches on a great many rabbit holes the team at Valve had to deep dive into to make the technological advances they deemed necessary for Half-Life 2 happen. Not understanding even a little bit of the technical details, it was also the first time I was confronted with the idea that games actually go through a process of creation, where each and every detail is meticulously crafted, rather than magically appearing on store shelves when the time is right.

Back then, games were proudly marketed with their technological and technical advancements, whereas today it appears to be more implicit. I feel that putting the hard work that went into games on display got lost or pushed into the background somewhere between our expectations rising over time, the supply of low-hanging fruits drying up, as well as gaming becoming more mainstream. After having been through that much backlash for downgrading games’ graphics between their pre-release material and the actual released product, understandably we also rarely see testing levels and other less polished footage of games.

Hard to say exactly why though. My guess is that, while the craft and art behind video games still holds a very high value, the industry has become split between large productions that are playing it safe trying to appease shareholders, and independent developers who generally lack the funds to push the envelope in the same way as back then. Pushing the envelope simply got very expensive and time-consuming. And despite being on a big budget, a mainstream series like Call of Duty wouldn’t be able to ship some bleeding edge features, because it has different priorities. It needs to run well on a wide range of systems to retain its players, so the studios working on it have to progress in lockstep with their slowest targeted systems. Undoubtedly, graphics is also generally not one of Call of Duty’s main attractions, it was never marketed primarily on that. In my eyes, Call of Duty is more importantly an exercise in storytelling (aside from the very popular multiplayer), where the teams appear to show increasingly impressive animation work.

Just recently, Death Stranding 2: On The Beach was widely covered for its TGS presentation, where its photo mode featuring their impressive character tech was shown off, going above even the first Death Stranding, which was already mindblowing.

Everything about this presentation looks really convincing, and it was one of the main talking points in the coverage of it. Though, officially, discussion of the tech behind it all is of course absent, aside from shots from motion capturing for the game.

The last time I remember there being somewhat deeper technical discussion was around the release of Unreal Engine 5, introducing their new technologies Nanite and Lumen, and later, developer-centric demos that were published by gaming outlets, like a demo of the procedural generation tools in Unreal Engine 5.2. Players were discussing the implications for games in development because of Epic’s promises of a relatively easy upgrade path.

On the other hand, these days you have small studios, and even individual creators who provide lots of insight into their development process. But their strengths lie elsewhere, as they most often innovate in terms of gameplay and storytelling, rather than rendering tech for example.

While I’m happy that the demoscene is still living and outlets like Digital Foundry exist to cover some of the advances made as far as they can with a view from the outside, I would love for the industry to return to boasting their technical achievements more. And to celebrate what’s already there, I made a list of my favorite tech showcases:

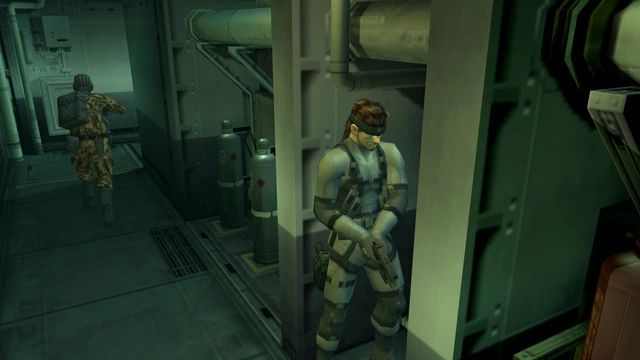

Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty E3 2000 trailer (2000)

ATI Radeon’s Ark tech demo (2000)

Janky pre-release gameplay footage of Shrek (Xbox), the first commercial game using deferred rendering (2001)

Nvidia Nalu tech demo (2004)

The Toughest Enemy DirectX9 demonstration trailer for S.T.A.L.K.E.R. Shadow of Chernobyl (2005)

Heavy Rain E3 2006 tech demo trailer (2006)

Metro 2033: The Last Refuge E3 2006 tech demo trailer (2006)

Nvidia Froggy tech demo (2006)

Nvidia Box of Smoke tech demo (2006)

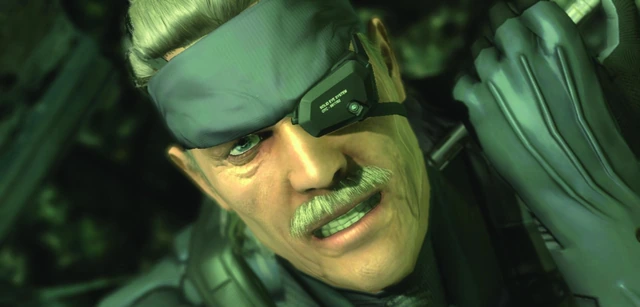

Metal Gear Solid 4 TGS 2006 tech demo (2006)

Trailer for CellFactor: Revolution - the first game using the AGEIA PhysX physics accelerator card (2006)

Naturalmotion’s Euphoria tech demo (2008)

Dunia Engine tech demonstration trailer for Far Cry 2 (2008)

From Dust tech demo (2010)

Crysis 3 tech demo trailer (2012)

Nvidia A New Dawn tech demo (2012)

Get Even “What is real” trailer (2014)

Deus Ex: Mankind Divided E3 2015 tech demo trailer (2015)

Agni’s Philosophy - Final Fantasy tech demo (2016)

Teardown announcement (2019)

Nvidia Marbles at Night RTX tech demo (2020)

SuperRT SNES raytracing demo (2020)

Portal with RTX reveal trailer (2022)

Hellblade 2: Senua’s Saga Metahuman demo (2023)