Tea Shop

A first person mystery horror adventure about unraveling a ghost town's past and coping with the happenings.

Tea Shop is the working title for a first-person horror adventure game I worked on during my Bachelor’s degree studies at Cologne Game Lab. Giovanni Tagliamonte and I proposed the concept and had a whole semester to refine it and build a game around it.

A foggy day in the woods.

How Mundane Can Horror Be?

One critical piece of the concept is an exploration of ways to transition the player from mundane everyday situations into horror scenes and back in an open-world context.

The Design

We saw the biggest challenge to be having players intuitively control the balance between creepy and comfy scenes themselves in a way that would allow the storyline to progress at a pace that felt right to us. The game had to provide enough base mechanics, systems and, importantly, things to do outside of progressing the story, which is where we thought most of the creepy scenes would lie. At the same time, the world had to be designed in a way that allows for rapid transitions between creepy and comfy without being jarring.

The Story Sketch

It is the 1980s. The player slips into the role of a psychologically disturbed misanthrope, living life as peacefully as possible while recovering from their illness in a secluded hut near the Canadian village of Autumn Well. One day, waiting for their groceries and medications to be delivered, they find the entire village turned into a ghost town from one moment to the next. This is where creepy happenings start to haunt the village and its outskirts. It’s on the player to figure out what happened and how the happenings are connected to the village’s sinister past.

We based Autumn Well’s general direction loosely on Bright Falls of Alan Wake. Remedy managed to capture North American forests in a convincing way that resonated with us and we wanted to combine that atmosphere with an even further secluded setting. Another game that also did it for me, though it came after Tea Shop, is parts of We Create Stuff’s In Sound Mind.

Tying it Together

Given the main character’s disposition, we decided for their flawed mental state to be the driving factor for the gameplay and the horror elements. They would be the game’s unreliable narrator.

Throwing a mentally unstable person into creepy situations without acknowledgement would create a huge ludonarrative dissonance. The game required an opposing force to counteract the horror scenes. And this is where the other part of the gameplay elements would take over. The horror setpieces were designed to have little interaction and no combat, meant to be mostly experienced by players simply by walking around and triggering things to happen. The experience predictably would wear down the main character, and they would subsequently need to calm back down and cope with the happenings.

The player’s hut at night (brightened for convenience).

To create a comfy atmosphere and accelerate this process, we designed a range of repetitive and mindful tasks the player could do while outside the horror setpieces. One of the more intricate ones implemented is preparing tea, which tied into the interaction system. We also planned stargazing, walking in the woods at daytime, getting groceries from the supermarket, topping up the generator out back to keep the lights on, and more. Additionally, the main character’s mental state would get small bonuses for other comfy-feeling situations and interactions, like locking the hut’s front door at night, being indoors while it’s raining, making the bed in the morning, etc.

For these survival game-esque upkeep tasks, this concept led us to coin the term “Mundane Survival Horror”.

Where the Horror Lives

Of course, all of the mundane elements of the gameplay loop would be useless without some good ol’ horror setpieces!

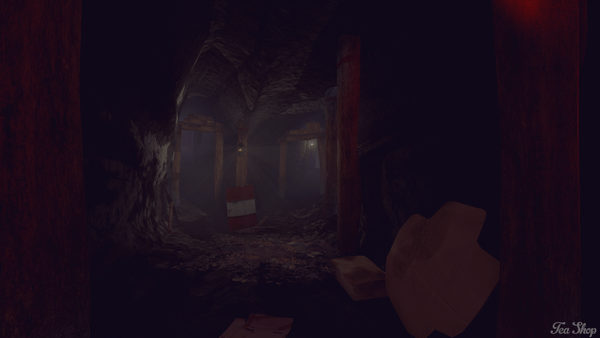

A closed-off mine leading to tunnels connected to the MKUltra R&D site (brightened for convenience).

The village’s backstory is partially tied to operations part of the US’ MKUltra project. In one of the implemented setpieces, the player would visit a long-abandoned R&D site and would uncover the happenings there when the site was still active, and its ties to the public services of Autumn Well.

The main loop behind the horror setpieces is leading the player deep inside and have them chased back out after reaching a conclusion or story beat. In case of the R&D site, the player would explore the way to the site, reading documents and learning about the place they’ve stumbled into. Along the way, they would find dusty offices, bedrooms, a cafeteria and some slight scares and eerie atmosphere.

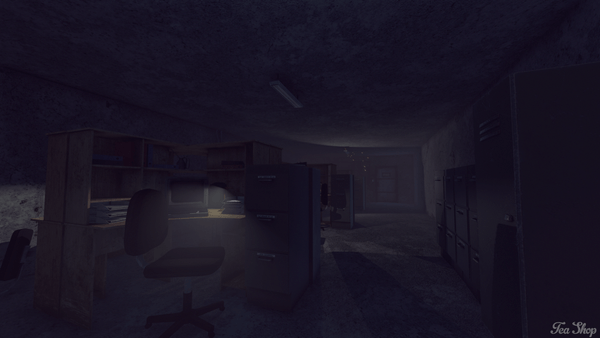

Here, the unreliable narrator-aspect comes into play. Instead of seeing the place as it is, the main character would substitute a skewed view of reality in an attempt to repress the creepy atmosphere. One example of this would be that the whole site has electricity and some of the lights are on.

An office with computers, unreliably reconstructed by the main character (brightened for convenience).

The reality-repressing effect gradually fades as the player eventually finds the site itself, burned down and singed, presumably as part of cleanup operations. The exploration ends in the pristine-looking director’s office and a document explaining the goings on at the site, and tying it to failures of public services that led to the village’s school closing years ago. A surreal chase takes place after the player finds the door to the director’s office suddenly opening to another office near the site’s entrance, with lit candles all over all the way to the exit.

Reflection

Tea Shop was an extremely enlightening project to have worked on. The concept pushed us to innovate on many different fronts. Some of the experiments panned out, and some didn’t. While I’d call the experiment of the concept itself successful, it was limited by the scope we had to confine ourselves to. And even then, the scope was a good bit too big for us, because the concept requires a believable open-world environment and tightly designed horror setpieces at the same time.

In my mind, in terms of systems design, the most difficult aspect to get right was the inventory and two-hand interaction system that allowed us to create intricate multi-step interactions for the aforementioned tea-making process for example. It was partly bogged down by a hasty implementation, making interactions slightly unreliable, and frustrating as a result. To me, conceptually, its clunkiness was a valid representation of the main character’s mental state - depressed and unwilling to do the upkeep tasks. Though we likely would have explored a different mode of interaction if we went further with the project to make it more accessible.

The other part that was extremely challenging was simply making the player leave their house, and balancing inaction and penalties. Being an open-world game, technically the player was free to roam around and ignore whatever the game requests from them. The mundane survival element helped, requiring some upkeep that forced the player to go outside eventually, but the moments where penalties to the main character’s started to kick in, felt contrived and out of left field. This part definitely still needed refinement.

All in all, the juxtaposition of creepy and comfy worked really well though. We were able to implement multiple convincing setpieces that were able to play out their creepy horror vibe to a greater extent precisely because the rest of the game is so focused on calming exercises and routines.